CoSMoMVPA concepts¶

Dataset¶

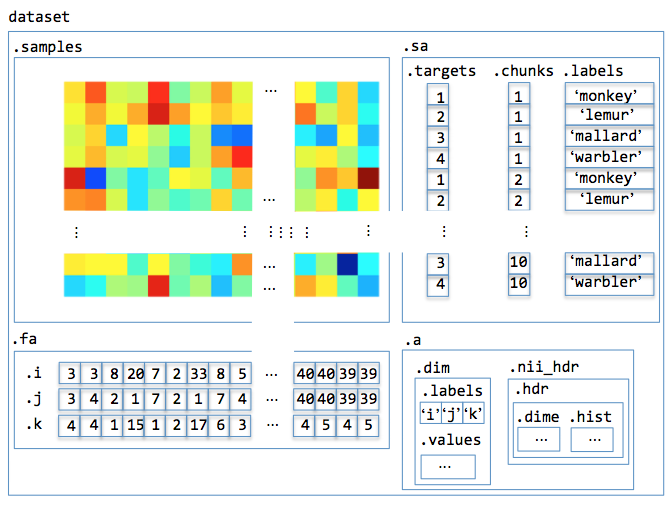

Given the general formulation of patterns as used in MVPA, this section will describe a framework that can be used to to MVPA in Matlab easily. Inspired by PyMVPA, the matrix representation of patterns is expanded to form the concept of a Dataset, which contains:

a sample-by-feature data matrix.

sample attributes: attributes for each sample (row) in the data matrix.

feature attributes: attributes for each feature (column) in the data matrix.

dataset attributes: general attributes that are not linked specifically to samples or features.

In analogy with a table with data, the sample attributes can be seen as the row headers and the feature attributes as the column headers. However, each sample and feature (i.e. row and column) can have multiple attributes associated with them.

For example, an fMRI dataset in CoSMoMVPA can be visualized as follows:

A more detailed explanation is provided below.

Attributes¶

Just the data in the sample-by-feature data matrix not sufficient to be able to perform analyses; typically one needs additional descriptors (or attributes) indicating what a sample or feature represents. In the Dataset representation used in CoSMoMVPA, there are three types of attributes:

Sample attributes¶

Sample attributes contain information about each sample (and is the same across all features), and are stored in a field .sa. Most MVPA requires at least the following two sample attributes:

.sa.targets: represent the class of each sample. In the fMRI example above, these would be the category of the stimulus (monkeys, lemurs, ladybugs or lunamoths). In CoSMoMVPA, these are represented numerically; for example, 1=monkey, 2=lemur, 3=ladybug, 4=lunamoth).

.sa.chunks: samples with the same chunks represent a group of samples that is acquired ‘independently’ from samples in other chunks. Independently is hard to define precisely, but in fMRI it usually refers to a single run of acquisition. In the fMRI example above, there are 10 chunks, each with 4 samples. In a take-one-out cross-validation analysis, for example, one tests a classifier on the samples in one chunk after it has been trained on the samples in the remaining chunks.Note that in the example here there is a third sample attribute,

.sa.labels, which is a cell containing human-readable descriptions of each sample.

Feature attributes¶

Feature attributes contain information about each feature (and is the same across all samples), and are stored in a field .fa. These are optional in principal, but in most use cases these are used to specify information where the feature came from.

in fMRI: the voxel indices associated with each feature. With three spatial dimensions each feature is associated with three indices,

.fa.i,.fa.j, and.fa.k.in MEEG: the indices of SQUID sensor, time-point, or frequency band. For example, data transformed to time-frequency space has three feature attributes:

.fa.chan,.fa.time, and.fa.freq.

Dataset attributes¶

Dataset attributes contain general information about the whole dataset.

In fMRI these are typically:

A

.a.volfield containing information about the voxel-to-world mapping. This is required to map the spatial location of each voxel from voxel coordinates (integer indices) to world coordinates (metric units, typically millimeters). Currently this is stored in a 4x4.a.vol.mataffine transformation matrix that follows theLPI(left-to-right, posterior-to-anterior, inferior-to-superior) convention (non-affine transformations are currently not supported).The range of indices used in

.fa.i,.fa.jand.fa.k, stored in.a.fdim.values.The names of the spatial feature attributes, stored in

.a.fdim.labels.In MEEG these are, for a dataset with data in time-frequency space:

The names of the feature attributes (

chan,time, andfreq), stored in.a.fdim.labels.channel names are stored in the field

.a.fdim.values{1}, time-points in.a.fdim.values{2}, and frequencies in.a.fdim.values{3}. In such a dataset, the feature attribute.fa.chan,.fa.time, and.fa.freq, contain integers that index the corresponding elements in.a.fdim.values.

Targets¶

The example above showed the sample attribute targets, and its use is not by accident. As for almost all MVPA applications one is interested in the (dis)similarity of patterns within and across conditions of interest, these should be stored in the dataset. Here, conditions of interest is typically defined by the experimental paradigm, for example:

category of visual stimulus: house, face, or human body.

effector involved in movement planning: left hand or right hand.

whether a peri-threshold auditory stimulus was perceived: yes or no.

In CoSMoMVPA these conditions are coded in a special sample attribute called targets, i.e. in a dataset ds they are in ds.sa.targets. They should be coded as integer values in a Px1 vector, where P is the number of samples.

Chunks¶

Another sample attribute illustrated above (that is also important for most MVPA applications) is the concept of chunks. Here, a chunk is meant to indicate a set of samples that can be considered independent from samples in other chunks, whereas samples within a chunk are not necessarily independent.

Independence is crucial here, because many core MVP analyses assess generalizability of pattern properties of a subset of chunks to another disjoint subset of chunks. For example:

in split-half correlation analysis, the data is split in two and each half assigned to a different chunk, yielding two chunks. A typical application is computing ‘on-diagonal’ vs ‘off-diagonal’ correlations, i.e. the difference of pattern correlations of the same target versus other targets.

in an

n-fold cross-validation scheme, the data is split innchunks. A typical application is cross-validated classification, where a classifier is tested on one chunk after being trained on the remaining chunks.

- Typical chunk assignments are:

in fMRI studies: each run (period of continuous recording) gives rise to a single chunk. Putting samples in a single run in different chunks may violate the independency assumption because of the slow-ness of the BOLD response, unless samples are separated by a considerable time interval.

in MEEG studies: if trials can be assumed to be independent (which most people in MEEG studies seem to do), then chunks can be assigned randomly (or in a systematic order). This can be done pseudo-randomly using cosmo chunkize. If the indendency assumption cannot be fulfilled then chunks should be assigned on a run-by-run basis.

As with targets above, chunks should be coded as integer values in a Px1 vector, where P is the number of samples.

Samples + sample attributes + feature attributes + dataset attributes = dataset¶

Taken the above together, a CoSMoMVPA dataset contains four ingredients: ‘samples’ (the sample x features data matrix), ‘sample attributes’, ‘feature attributes’, and ‘dataset attributes’. These are implemented, in Matlab, using a struct, with fields .samples, .sa, .fa, and .a. For example an fMRI dataset can be instantiated using cosmo fmri dataset and might contain:

.samples,

[ 0.568 3.9 4.11 ... 0.732 0.473 2.37 1.45 3.71 4.86 ... -0.265 0.846 0.544 2.23 1.31 2.76 ... 0.314 0.485 -0.335 : : : : : : 2.06 1.46 3.52 ... -0.162 -0.00311 0.488 0.596 1.96 3.93 ... 0.147 1.16 3.14 -1.35 0.511 -0.116 ... -0.628 0.756 0.628 ]@40x298

.sa,

.targets [ 1 2 3 : 2 3 4 ]@40x1 .chunks [ 1 1 1 : 10 10 10 ]@40x1

.fa,

.i [ 44 42 43 ... 43 40 41 ]@1x298 .j [ 15 15 15 ... 16 19 19 ]@1x298 .k [ 3 4 4 ... 13 13 13 ]@1x298

and .a:

.fdim .labels { 'i' 'j' 'k' } .values { [ 1 2 3 ... 78 79 80 ]@1x80 [ 1 2 3 ... 78 79 80 ]@1x80 [ 1 2 3 ... 41 42 43 ]@1x43 } .vol .mat [ 3 0 0 -122 0 3 0 -114 0 0 3 -11.1 0 0 0 1 ] .dim [ 80 80 43 ]

In this case there are M=40 samples and N=298 features (voxels). Note that the sample attributes have M values in the first dimension, and feature attributes have N values in the second dimension. The information in the .fa and .a fields is used when the dataset is back to a volumetric dataset in cosmo map2fmri.

Dataset operations¶

Slicing¶

Slicing refers to selecting data in a dataset struct, either along the rows or columns. It is provided by the cosmo slice function, which takes three arguments: the dataset ds, indices or a mask indicating what to_select, and a dim argument indicating whether to slice along rows or columns.

Slicing samples (

dim=1; this is the default value) means that the specified rows are selected, both in.samplesand each field in.sa(such as.sa.targetsand.sa.chunks).Use cases include:

Select only samples for certain conditions (targets)

Select only samples in certain chunks; this is useful for:

cross-validation: data is tested using data in, say, one chunk after training on data in the remaining chunks (see cosmo nfold partitioner and cosmo nchoosek partitioner).

split-half correlations: when half of the data (in one (set of) chunks) is correlated with data in the other half (see cosmo oddeven partitioner and cosmo_correlation_measure).

Illustration of slicing rows (samples). In the masks, white elements are selected and black elements are not selected.¶

Slicing features (

dim=2) means that the specified columns are selected, both in.samplesand each field in.fa(such as.fa.i,fa.jandfa.kin an fMRI-dataset, which indicate the voxel indices). Use cases include:Select only certain voxels in a region of interest

Running a searchlight, which consists of doing the analyses many regions of interest.

Illustration of slicing columns (features). In the masks, white elements are selected and black elements are not selected.¶

Classifier¶

A classifier takes a training set of patterns, each with a target (class label) associated with them, and a test set of patterns, that have no targets associated with them. The patterns in the train and test set should be from disjoint sets of chunks, otherwise circular analysis will ensue (which is a Bad Thing).

In CoSMoMVPA, all classifiers use the same signature:

function predicted = cosmo_classify_lda(samples_train, targets_train, samples_test, opt)

where the inputs are:

samples_trainis aPxRmatrix forPsamples andRfeatures (i.e. it containsPpatterns).

targets_trainaPx1class label vector for each pattern insamples_train.

samples_testis aQxRmatrix withQpatterns, with no class labels associated

optis an optional struct may contain specific options to be used with a specific classifier.

The output predicted is a Qx1 vector containing the predicted class labels for each sample in samples_test. Classification accuracy can be computed by considering how many samples in the test set were predicted, and this can be compared to what may be expected by chance. In the simple case where each chunk contains the same number of n samples in each class, chance accuracy is 1/n. For MEEG datasets typically the number of samples in each class is not equal; the function cosmo balance partitions can be used to accomplish this.

Examples of classifiers are cosmo classify nn, cosmo classify svm, cosmo classify lda, and cosmo classify naive bayes.

A classifier is typically used to test how well data in a subset of the data generalizes to another, disjoint, subset of the data. Usually this is done by taking some chunks as a test set, and use the remaining classes as a training set; by repeating this process, each time taking different chunks to form the test set, one or more predictions can be made for each sample in a dataset. Dividing up a dataset in pairs of training and test sets is called partitioning, which is facilitated using cosmo nchoosek partitioner , and its special case, cosmo nfold partitioner. A classifier can be used for cross-validation using cosmo crossvalidate, or (see below), using a more abstract measure cosmo crossvalidation measure.

Note that, unless a measure, classifier functions are rather bare-bone as data structure; they do not operate on a dataset struct directly.

Measure¶

A dataset measure is a function with the following signature:

output = dataset_measure(dataset, args)

where dataset is a dataset of interest, and args are options specific for that measure. A measure can then be applied to either a dataset directly, or in combination with a ‘searchlight’ where the measure is applied to each searchlight separately. The output should be a struct with fields .samples (in column vector format) and optionally a field .sa - but no fields .fa and usually no field .a (except for a possible .a.sdim field, if the measure returns data in a dimensional format) .

For example, the following code defines a ‘measure’ that returns classification accuracy based ona support vector machine classifier that uses n-fold cross-validation. The measure is then used in a searchlight with a radius of 3 voxels; the input is an fMRI dataset ds with chunks and targets set, the output an fMRI dataset with one sample containing classification accuracies.

nbrhood = cosmo_spherical_neighborhood(ds,'radius',3); cv = @cosmo_crossvalidation_measure; cv_args = struct(); cv_args.classifier = @cosmo_classify_lda; cv_args.partitions = cosmo_nfold_partitioner(ds); sl_dset = cosmo_searchlight(ds,nbrhood,cv,cv_args);

Using classifiers and measures in such an abstract way is a powerful approach to implement new analyses. Any function you write can be used as a dataset measure as long as it uses the dataset measure input scheme, and can directly be used with (for example) a searchlight. When running a searchlight (cosmo searchlight) with a cosmomvpa_neighborhood (see above), data from .fa and .a from the neighborhood are combined with the .samples and .sa output from the measure to form a full dataset structure with fields .samples, .sa, .fa, and .a.

Examples of measures include:

Neighborhood¶

The traditional (volume-based fMRI) searchlight was introduced [KGB06] as a method to measure information content locally in the whole brain. In this approach, a sphere-shaped mask (usually with a radius of a few voxels) ‘travels’ through the brain, and at each location measures information content (such as correlation differences or classification accuracies). This process is done for each brain location, and the result assigned to the center voxel of each sphere. The result is an information (rather than univariate activation) map.

CoSMoMVPA overloads the searchlight concept through a more versatile neighborhood concept. A neighborhood definition describes a mapping that associates with each feature in the target domain (for the output) a set of features in the source domain (from the input). Neighborhoods are used for searchlight analyses (cosmo searchlight), where the concept of a traditional fMRI volumetric searchlight is generalized to other types of datasets as well. For example:

for a traditional volume-based fMRI searchlight, the features in the source and target domain are the same, and consist of the voxels.

for a surface-based fMRI searchlight, the features in the source domain are the voxels in the volume, whereas the features in the target domain are the nodes on the surface.

for an MEG-based searchlight with magnetometers in the time-locked domain, the source and target domain are the set of all combinations of magnetometers and time points.

for an MEG-based searchlight with planar gradiometers (

meg_planar) but with output as combined (meg_combined_from_planar) sensors, sensors in the source domain are the planar gradiometers and sensors in the target domain are the combined sensors.

A neighborhood is a struct with fields:

.neighbors: anNx1cell for N neighborhoods, where.neighbors{k}is a vector with features indices in the source domain associated with thek-th neighborhood.(optional)

.fathe feature attributes for the target domain. Each field element.fa.fieldshould haveNelements in the second (i.e. feature) dimension.(optional)

.athe dataset attributes for the target domain.(optional)

.origin, with subfields.aand.fa, with attributes in the source domain. If present, this information is used when a neighborhood is applied to a dataset: if they do not match the attributes, an error is thrown. This can help in accidentally using the wrong neighborhood for a particular dataset.

When running a searchlight (cosmo searchlight) with a cosmomvpa_measure (see below), data from .fa and .a from the neighborhood are combined with the .samples and .sa output from the measure to form a full dataset structure with fields .samples, .sa, .fa, and .a.

Neighborhood-related functions include:

cosmo spherical neighborhood: for fMRI spherical volume-based searchlight (c.f. [KGB06]), and MEEG source-space searchlight.

cosmo surficial neighborhood: for fMRI surface-based searchlight (c.f. [OWDD11]).

cosmo interval neighborhood: for MEEG searchlight for time or frequency domain (c.f. [LTO+14]).

cosmo meeg chan neighborhood: for MEEG searchlight over sensors.

The cosmo cross neighborhood can cross different neighborhoods, which provides functionality for:

fMRI time-space searchlight, if multiple time points are associated with each trial condition; achieved by crossing a spherical or surficial neighborhood with an interval neighborhood (for the time dimension).

MEEG time-space searchlight; achieved by crossing a an interval neighborhood (for the time dimension) with a channel or source MEEG neighborhood.

MEEG time-space-frequency searchlight: achieved by crossing two interval neighborhoods (for the time and frequency dimensions) with a third (channel or source MEEG) neighborhood ([LTO+14]).